Chapter 1. The Guests In Our Fields

The H-2a agricultural guestworker program in a nutshell

The agricultural economy of the Southeastern United States has always depended on a steady supply of artificially low-cost labor.

For more than 200 years, enslaved men, women, and children did much of the farmwork in North Carolina and surrounding states. Then it was mostly Black sharecroppers and tenant farmers who did this work; their way of life was only marginally better than slavery. When automobiles and highways came along, Black and poor White citizens tended to the crops here, migrating up and down the East Coast as the seasons changed, leading miserable lives as depicted in the landmark 1960 television documentary Harvest of Shame. Then, citizens of Mexico began working North Carolina’s fields, often without work authorization.

Today, a significant number of farmworkers in this state are Mexican dads authorized to do this work by way of the federal H-2A visa program. These so-called guestworkers leave their families in Mexico to spend the better part of a year planting, cultivating, and harvesting crops in faraway fields. Then they go home to spend time with loved ones before doing it again.

The H-2A program is nearly forty years old. It began in 1986 as part of the federal Immigration Reform and Control Act, or IRCA, which also made it illegal to hire job applicants lacking work authorization. Every H-2A job must be offered to a US citizen before a crop grower can hire a foreign worker to fill it.

But US workers won’t take these jobs. According to growers, this forces them to bring in foreign labor. Others disagree. They say there would be plenty of US applicants for farm jobs if workers were treated better and paid a fair-market wage—which growers say they cannot afford to do. The debate rages on. Meanwhile, the uncapped H-2A program lets growers bring in all the farmworkers they want, chiefly from Mexico, for one growing season at a time.[1]

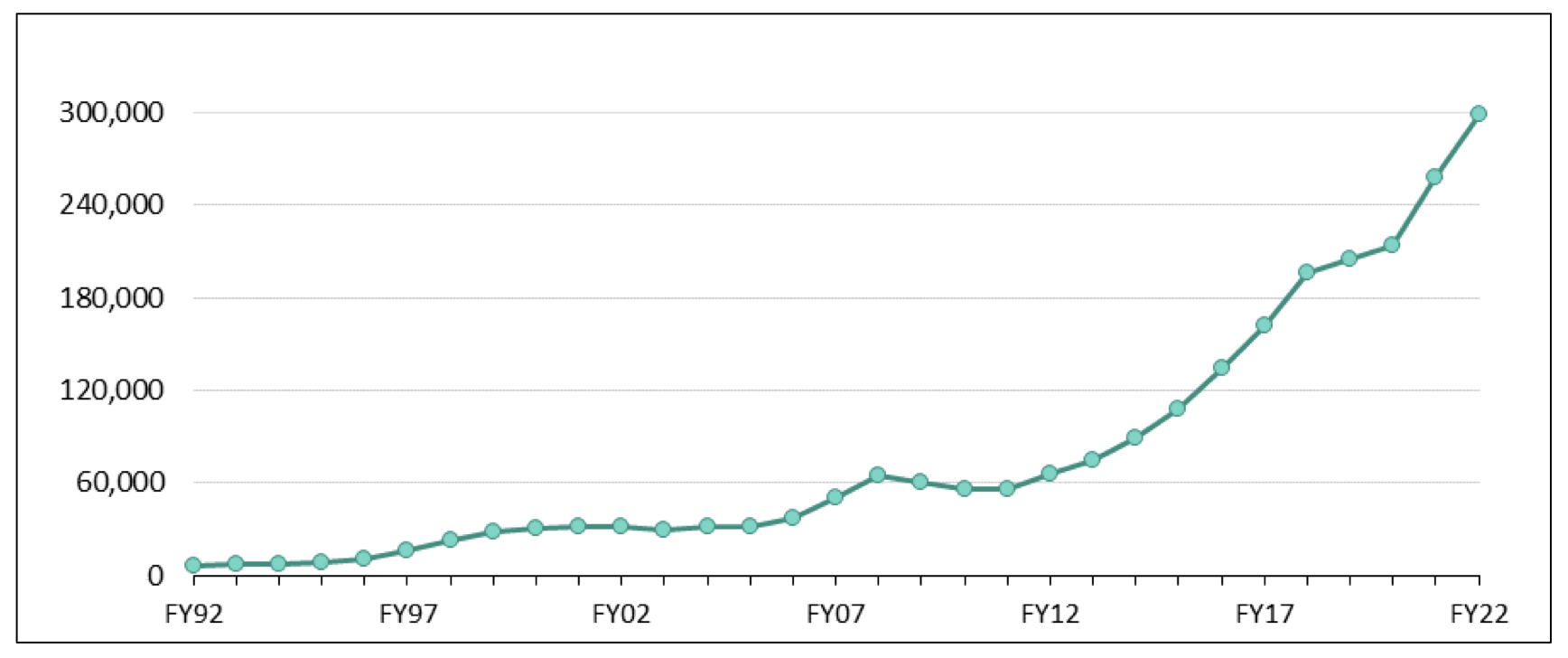

In 1987, the first year of the H-2A visa program, the United States certified 44 positions for work authorization. By 2014, that number had grown steadily to nearly 125 thousand. That’s roughly the size of Mexico’s army, it turns out. But the numerical coincidence did not last for long. By 2022, the number of H-2A visas had nearly tripled, climbing to 370 thousand. That’s more than the population of Cleveland.

[1] Mexico is not the only country providing H-2A workers, but 93 percent came from there in 2022. South Africa provided 3 percent; Jamaica 2 percent; and Guatemala 1 percent. The remainder came from countries including El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

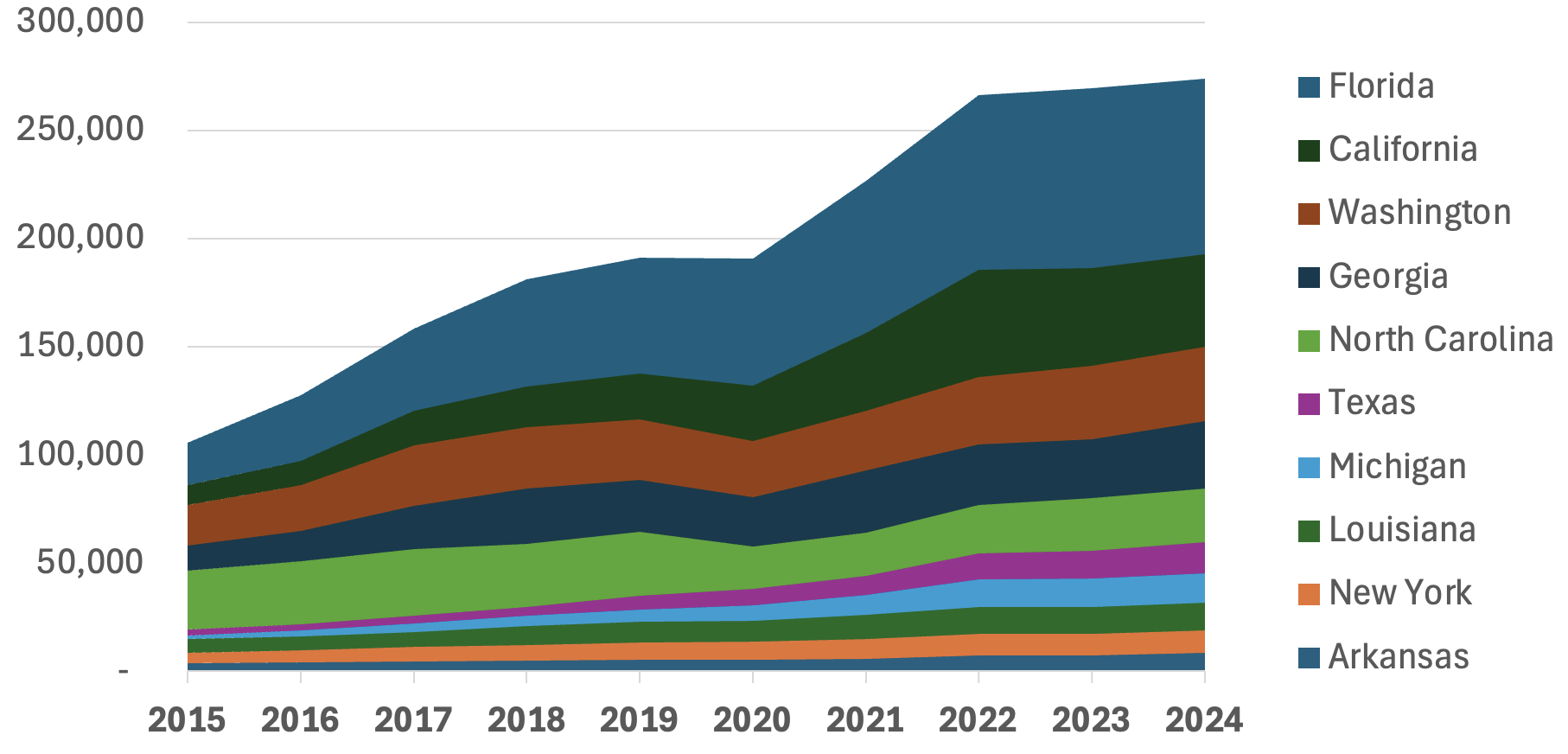

For many years, no other state received more H-2A farmworkers than North Carolina. That changed in 2017 when Florida took the lead. Now, most H-2A farmworkers can be found across five states: Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina in the Southeast, and California and Washington in the West. The growth in California and Washington has been especially sharp, with their numbers growing more than 1,000 percent over just the past ten years.

A sizeable H-2A workforce is a relatively new thing in those other states. Here, the program is beginning to show its age. Many of North Carolina’s H-2A farmworkers have been at this for decades, and many of our labor camps, which H-2A employers are required to provide at no cost to their workers, are decades overdue for repair. And our state legislature, long known for opposition to the advancement of worker rights in any industry, has had more time than other states to sharpen its elbows in its perpetual battle with farmworker advocates, keeping our farmworkers’ rights to a bare minimum.

Beyond its long history as a major employer of H-2A farmworkers, there are other reasons North Carolina is an especially good place to peer into this federal program.

Our agricultural roots run deep here, thanks chiefly to tobacco, a crop whose production is especially dependent on manual labor. Today, it’s our leading crop, just as it was nearly 400 years ago, and no other state comes even close to producing more of it. We are also the top producer of sweet potatoes, the second-largest producer of Christmas trees, a leading producer of berries, and a steadfast provider of peppers, melons, grains, and dozens of other crops whose production depends on manual labor.

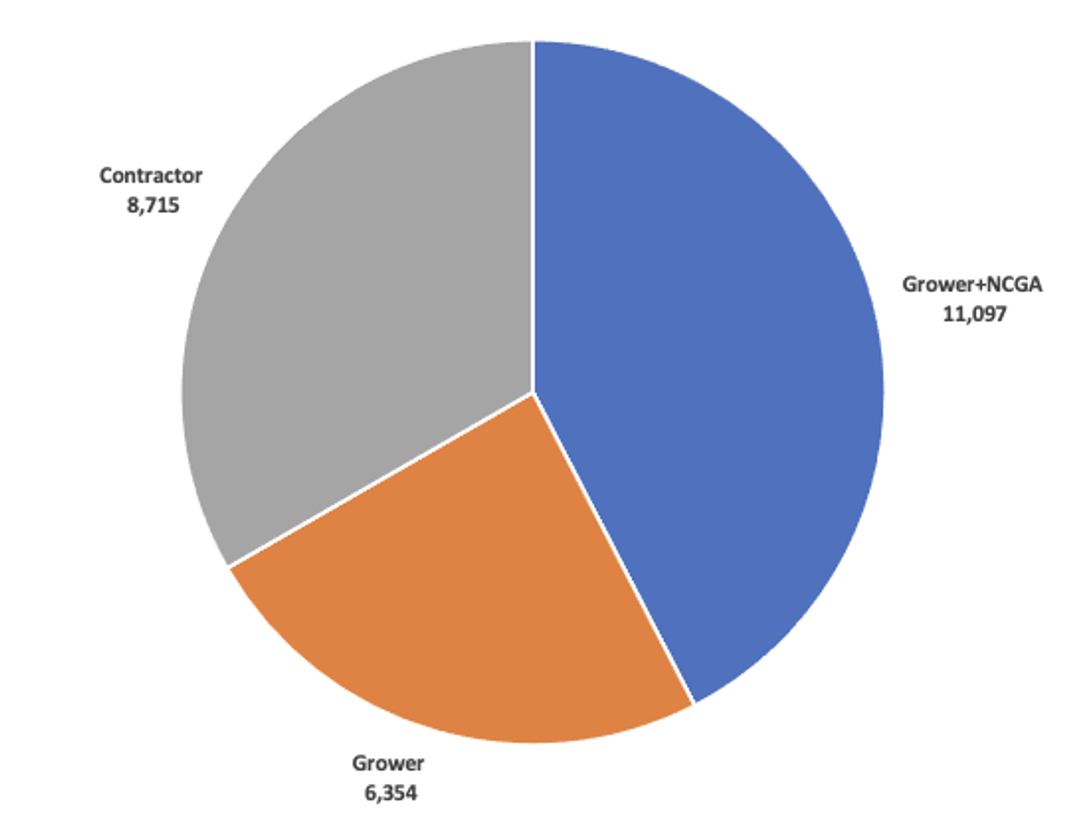

The nation’s largest single employer of H-2A farmworkers is here. Year after year, the North Carolina Growers Association, or NCGA, hires roughly nine thousand H-2A farmworkers, acting as a co-employer alongside a member grower. The NCGA story is an insightful one.

North Carolina is also the only state with a long-standing labor union created especially for H-2A farmworkers. The Farm Labor Organizing Committee, or FLOC, made history when it signed a collective bargaining agreement with the NCGA in 2004, entitling all NCGA farmworkers to union benefits. The union is struggling nowadays, for reasons both within and outside of its control. Still, like a boxer with a bloodied face who refuses to cede a fight, FLOC remains standing. Anyone curious about farmworker unionization could do worse than to know the story of FLOC.

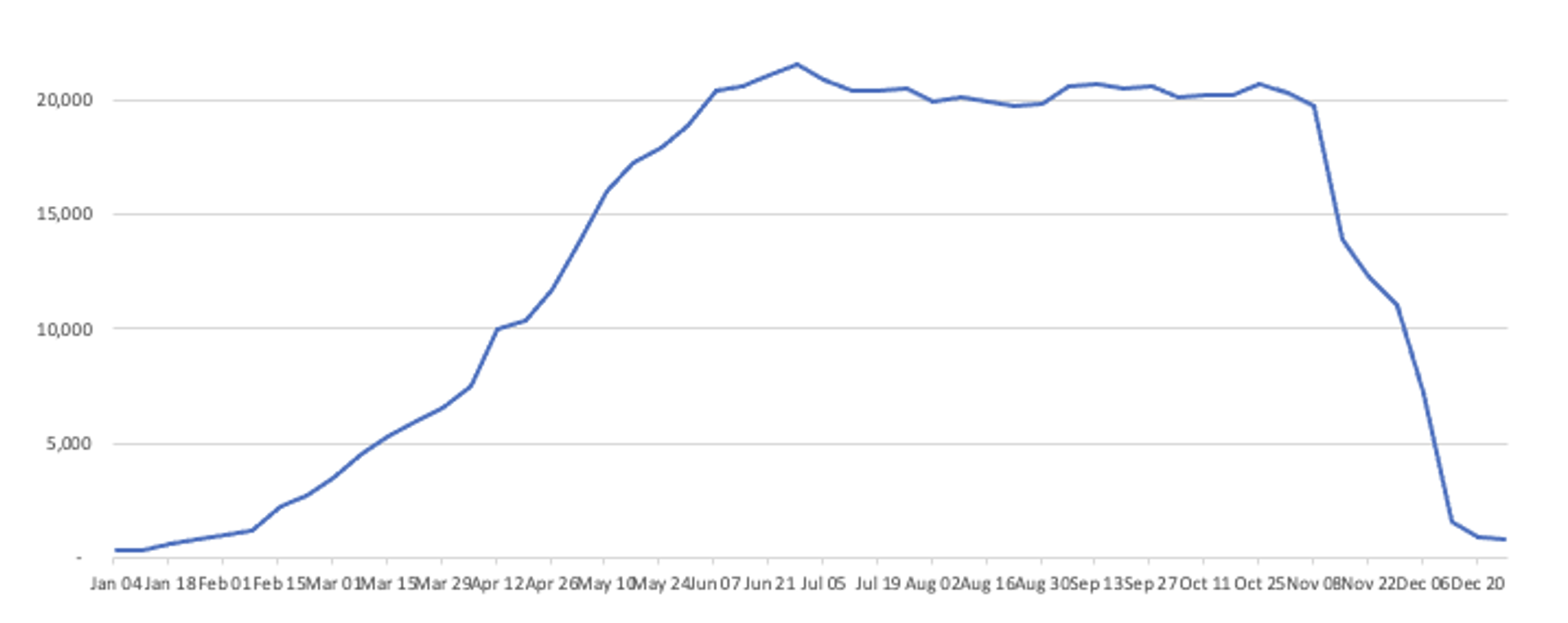

Each year, the US Department of Labor certifies roughly 25 thousand H-2A jobs for North Carolina employers.[1][2] Most arrivals begin in March and ramp up gradually until May. Departures are less gradual, with most workers leaving in November and early December.

[1] The number of workers filling jobs is something less than the number of certified positions. The NCGA, for example, as co-employer with a member grower, can move the same worker between two or more jobs with different contract periods.

[2] Like any number of government programs, there are numerous branches, agencies, and departments, at both the federal and state levels, involved in bringing H-2A farmworkers to US crop fields. The US Department of Labor (DOL) is the chief federal agency behind the program, determining how many workers are needed each year and processing employer applications at its national processing center in Chicago. Before the DOL work begins, a state workforce agency (SWA) has already certified an application and posted a job opening for the benefit of US citizens who might be interested. The DOL’s Wage and Hour Division is responsible for enforcing H-2A program requirements. The US State Department is also involved, issuing the actual H-2A visas to foreign workers at consulates abroad. And the US Department of Homeland Security (specifically, the US Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS) validates employer petitions for workers and, of course, checks papers before allowing individual workers to cross the border into the United States.

Where do our H-2A farmworkers do their work? There are farms employing them across North Carolina, with most in a cluster centered on the massive Sampson County. All five boroughs of New York City could fit into just this one county—three times over. Altogether, the “Sampson Ring” encompasses six thousand square miles of land, or more than twenty times the size of New York City.

As in other states, H-2A farmworkers are not the only ones doing crop work here. Many thousands of so-called seasonal workers live here year round, perhaps doing nonagricultural work during winter months and crop work during the warmer ones.[1]

There are also several thousand so-called traveling migrant farmworkers, a throwback to an earlier era, who remain in the United States year round, moving with the seasons, working, say, citrus in Florida during the winter, then moving up the coast to other states for the rest of the year.

Many seasonal and traveling migrant farmworkers lack work authorization. For this and other reasons, it is difficult to gauge the total population of crop workers in North Carolina. Opinions regarding the true count vary, but the consensus seems to be around 75 thousand.[2]

Knowing that growers wishing to hire H-2A farmworkers first must try to find American workers, you might picture them posting job ads then waiting to see how many US citizens apply, and only then seeking foreign workers. But there is no time for such a linear process. Ready or not, a new growing season begins with each of our trips around the sun. For growers to comply with the so-called “positive recruitment” requirement of the H-2A program, an administrative ritual ensures growers have all the workers they need, when they need them.

Things begin at the end of each year when a prospective employer submits an H-2A Agricultural Clearance Order Form ETA-790A, known colloquially as a job order, which before long appears on the Department of Labor’s Seasonal Jobs website.[3] Anyone can search here for temporary agricultural H-2A jobs, as well as nonagricultural H-2B jobs. Digging further, one can view the original job order, whose job descriptions can be enlightening. Here’s a bit of one:

[1] H-2A farmworkers also work seasonally, but the term “seasonal worker,” as I've heard it used, tends to refer to those who live in the US year round.

[2] Nationally, while the number of H-2A farmworkers is growing each year, they still comprise only a third or so of all agricultural wage workers in the United States, of which there are something like one and a half million.

[3] https://seasonaljobs.dol.gov/

Work is to be done in the field for long periods of time . . . Workers will assist in loading trucks with product weighing up to and including 60 pounds and lifting to a height of 5 feet for long periods of time. Workers should be able to work on their feet in bent positions for long periods of time. Work requires repetitive movements and extensive walking . . . Workers are exposed to wet weather early in the morning through the heat of the day, working in fields. Temperatures may range from 10 to 100 F.

Some writers of job descriptions forget to turn off their caps-lock:

WORKERS MUST BE ABLE TO PERFORM ALL WORK ACTIVITIES WITH ACCURACY AND EFFICIENCY. INSTRUCTIONS AND OVERALL SUPERVISION AND DIRECTION OF THE WORKERS WILL BE PROVIDED BY A COMPANY SUPERVISOR. ALL WORKERS HIRED PURSUANT TO THIS LABOR CERTIFICATION MUST BE ABLE TO COMPREHEND AND FOLLOW INSTRUCTIONS OF A COMPANY SUPERVISOR AND COMMUNICATE EFFECTIVELY TO SUPERVISORS. UNUSUAL, COMPLEX, OR NON-ROUTINE ACTIVITIES WILL BE SUPERVISED. EMPLOYER RETAINS FULL DISCRETION TO MAKE WORK ASSIGNMENTS, TAKING INTO ACCOUNT UNFORESEEN CIRCUMSTANCES SUCH AS WEATHER OR OTHER UNSCHEDULED/UNEXPECTED INTERRUPTIONS IN REGULAR WORK. ALL WORKERS MUST PERFORM THE WORK ASSIGNED BY THE FOREMAN OR CREW BOSS. WITHOUT SPECIFIC AUTHORIZATION BY THE FOREMAN OR CREW BOSS, WORKERS MAY NOT PERFORM DUTIES WHICH ARE NOT PROVIDED FOR IN THIS APPLICATION, OR WORK IN AREAS NOT ASSIGNED. WORKERS WILL BE EXPECTED TO PERFORM ANY OF THE LISTED DUTIES AS ASSIGNED BY HIS/HER SUPERVISOR. WORKERS MAY NOT LEAVE THEIR JOB ASSIGNMENT AREA UNLESS AUTHORIZED. LEAVING JOB AREA OR FARM WITHOUT PERMISSION MAY BE CONSIDERED VOLUNTARY RESIGNATION. PRIOR TO BEGINNING WORK ON OR AFTER THE DATE OF NEED, WORKERS WILL BE REQUIRED TO ATTEND AN ORIENTATION ON WORKPLACE RULES, POLICIES, AND SAFETY INFORMATION. WORKERS SHOULD BE ABLE TO PERFORM REPETITIVE MOVEMENTS, ENGAGE IN EXTENSIVE WALKING, AND WORK ON FEET WHILE IN BENT POSITIONS FOR EXTENDED PERIODS OF TIME. ALLERGIES TO ITEMS SUCH AS RAGWEED, GOLDENROD, INSPECT SPRAY, AND RELATED CHEMICALS MAY AFFECT WORKERS’ ABILITY TO PERFORM THIS JOB. WORKERS SHOULD BE PHYSICALLY ABLE TO DO THE WORK REQUIRED WITH OR WITHOUT REASONABLE ACCOMMODATION. WORK IS TO BE DONE FOR LONG PERIODS OF TIME. TEMPERATURES MAY RANGE FROM BELOW FREEZING TO 105 F. WORKER MAY BE REQUIRED TO WORK IN IN WET CONDITIONS AND SHOULD HAVE SUITABLE CLOTHING FOR VARIABLE WEATHER CONDITIONS. WORKERS MAY BE REQUIRED TO WORK DURING OCCASIONAL SHOWERS NOT SEVERE ENOUGH TO STOP FIELD OPERATIONS. SATURDAY WORK IS REQUIRED OF ALL WORKERS. ALL WORKERS MUST BE ABLE TO LIFT/CARRY 60 LBS. EMPLOYER MAY REQUIRE POST-HIRE DRUG TESTING UPON REASONABLE SUSPICION OF USE AND AFTER A WORKER HAS AN ACCIDENT AT WORK. EMPLOYER WILL PAY FOR SUCH DRUG TESTING. ALL WORKERS MUST OBEY ALL SAFETY RULES AND BASIC INSTRUCTIONS AND BE ABLE TO RECOGNIZE, UNDERSTAND AND COMPLY WITH SAFETY, PESTICIDE WARNING/RE-ENTRY AND OTHER ESSENTIAL POSTINGS. THE JOB REQUIRES EXTENSIVE STANDING AND WALKING. WORKERS ARE FREQUENTLY REQUIRED TO USE THEIR HANDS AND ARMS TO HANDLE, FEEL, REACH, CLIMB, OR BALANCE. WORKERS ARE OCCASIONALLY REQUIRED TO STOOP, KNEEL, CROUCH, OR CRAWL UNDER LINES. WORKERS MUST BE ABLE TO LIFT/CARRY UP TO 60 LBS. THROUGHOUT THE COURSE OF THE DAY. SOME WORKERS WHO HAVE A LEGAL DRIVER’S LICENSES MAY BE NEEDED TO DRIVE A TRUCK OR BUS TO AND FROM FIELD. WORKERS MUST BE ABLE TO PERFORM ALL DUTIES WITHIN THIS JOB DESCRIPTION IN WHAT CAN BE CONSIDERED A SAFE MANNER ADHERING TO ALL ESTABLISHED SAFETY GUIDELINES, PRACTICES, AND PROCEDURES. SUPPLEMENTAL TO OTHER TASKS, WORKERS MAY PERFORM VARIOUS DUTIES ASSOCIATED WITH INSTRUCTING OTHER WORKERS ON HOW TO COMPLETE JOB DUTIES AS NEEDED AND TIME KEEPING. SUPPLEMENTAL TO OTHER TASKS, WORKERS THAT ARE ABLE TO BE PROPERLY LICENSED MAY ALSO TRANSPORT WORKERS. WORKERS MAY BE REQUIRED TO DRIVE FORK-LIFTS, DUMPCARTS, AND SKIDSTEERS. WORKERS MAY BE REQUIRED TO FILL OUT SHIPPING PAPERWORK.

Few US jobseekers apply for jobs at the DOL website. Virtually every job posted there is ultimately filled by a farmworker from Mexico or another foreign country. For the 2022 growing season, after advertising nearly ten thousand jobs open to anyone, the NCGA received applications from just three US workers. Two of them were given a job. Neither showed up.

The positive recruitment requirement is not the only rule H-2A employers must follow—the full description of all rules fills many pages. They must also pay an hourly wage that ostensibly will not discourage a US worker from taking those jobs, known wonkily as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate. The AEWR is a “super” minimum wage for agricultural guestworkers, set per state by the federal government. States may have a minimum wage that exceeds the AEWR.

Beyond agreeing to pay the AEWR, the so-called “three quarter rule” requires that employers commit to provide work for at least 75 percent of the time workers are here. If a worker comes from Mexico for, say, an eight-month contract, they might work for only six. The workers know this, of course. It’s all spelled out in their contract. But they might not consider two things. First, they need to bring from Mexico enough money to last until the first paycheck. Second, once they start working, they need to decide on each payday how much to send home and how much to keep on hand in case work dries up. It’s a tricky calculation, especially if there’s a family at home in Mexico depending on that money to put food on their own table.

Employers must agree to not charge workers a recruiting fee for H-2A jobs. They must also pay for transporting workers to and from their places of residence and provide housing that meets federal and local standards.

There are roughly 1,600 labor camps for the housing of H-2A farmworkers in North Carolina, spread across 86 of the state’s 100 counties.[1]Most are in and around Sampson County on the eastern side of the state.

[1] North Carolina is the only state with a remarkably tidy one hundred counties. A few states have more counties, and many have fewer, but only North Carolina has exactly one hundred.

The sizes of North Carolina farm labor camps vary widely. One might be a single mobile home for one worker, while another might be a giant complex of structures with beds for several hundred. Quality varies too. The state has clear health and safety requirements for migrant labor camps, and a team of state inspectors charged with enforcing them. By contemporary housing standards, however, those standards are relatively low. And the inspection process is imperfect. As a result, camp quality is largely at the discretion of whoever who owns the camp.

The quality of some camps is on par with what you might find at a university dorm: decent furnishings and appliances, adequate heating and cooling, and clean kitchen and bath facilities. Other camps are no place anyone would choose to spend a night: Perhaps neither heated nor cooled, or with aging appliances or disgusting toilet facilities, or rotting mattresses decades overdue for replacement. Nobody can say with authority how many camps are like the former and how many are like the latter. But certainly, some workers enjoy decent housing while others do not.

All H-2A farmworkers suffer the hardship of long-term separation from family—as of course do other members of those families. Most workers suffer as well from isolation, confined to work sites and labor camps for most hours of every week, in a country where they don’t speak the language. Some workers endure dangerous working conditions, forced to work in lethal heat with inadequate water or breaks, and very few have any means for reporting grievances.

It’s easy to fault growers for poor housing and other H-2A farmworker hardships. Too easy. One cannot understand the lot of the farmworker without understanding the hardships facing the grower. The pressure on a typical North Carolina grower to stay afloat, to continue the family business for the next generation, is one that few people outside of agriculture can appreciate.

At the core of any grower’s challenge is uncertainty. The risks are numerous: unpredictable weather, increasing costs of fuel and other things they must buy, changing market prices for the crops they grow, and more. Any one of these might wipe out any profit one year. Or for several years.

Listening to growers, one hears again and again how difficult it is to pay the required H-2A minimum wage, or AEWR. In North Carolina, that wage for 2022 was $14.16. By 2025 it had grown to $16.16. That’s a 14% increase in three years, or almost 5% annually. The grower’s direct competition, foreign growers of the very same crops sold in the very same stores in the US, can pay just a fraction of the AEWR to their workers.

One can presume that, even with constant challenge of simply staying in business, most H-2A employers treat their workers as best they can. But they have a powerful upper hand over those workers that some employers take advantage of. As every H-2A contract is for one season only, employers get to choose who can come back to work another year and who cannot. That power imbalance, unthinkable in most other legitimate industries in the United States, can lead to the mistreatment of workers, from making them sleep on poor mattresses to working them beyond the point of exhaustion. With no jobs at home that pay like these do—an hour’s pay here can take two days to earn there—plenty of Mexican laborers will put up with such treatment.

The power imbalance is baked right into the legal system in which the H-2A program resides, where laws tend to favor growers, each of whom can appeal to their elected officials that laws be tailored to their needs. Of course, not a single H-2A farmworker can appeal to their representatives in the US Congress. They don’t have any. The H-2A farmworker is nobody’s constituent.

All farmworkers in the United States, citizen and noncitizen alike, are subject to a sadly outdated feature of our labor laws. It’s known asagricultural exceptionalism and refers to the enervating fact that federal law exempts farmworkers from some of the basic rights other US workers have, such as the right to join unions under the National Labor Relations Act. Nor are agricultural workers generally covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, whose features include minimum wage guarantees and bans on most, but not all, child labor. One FLSA right fully denied farmworkers is the right to be paid time and a half after working eight hours in a day or forty hours in a week. Farm work is exceptionally hard work. If anyone deserves overtime pay, one might reasonably think it’s our farmworkers.

Some states provide legal protections denied to agricultural workers at the federal level. California and New York, for example, grant farmworkers rights to join unions. They also have laws providing overtime pay to farmworkers.

Here in North Carolina, state law heavily favors the interest of the employer over that of the farmworker. Passage of the 2017 Farm Act, for example, made it illegal for growers to even recognize a farmworker union in the settlement of a lawsuit. And state law governing wages and whatnot could not be clearer on this key point: Farmwork is completely exempt from any of the provisions of the North Carolina Wage and Hour Act. Not just exempt, mind you, but “completely” exempt. That Wage and Hour Act is kind enough to promote the general welfare of the people here, but only without jeopardizing the competitive position of North Carolina business and industry. Business and industry come first. People second.

Roughly two thirds of North Carolina’s H-2A farmworkers are hired by the individual or family who owns a farming operation, either directly or by way of the NCGA. The rest are hired by farm labor contractors, or FLCs. Also known as crew leaders, or contratistas, these are supervising intermediaries between growers and workers.[1] Contractors are responsible for recruiting workers in their home country, getting them to North Carolina, housing and feeding them, transporting them to and from the fields, and paying them.

[1] The term mayordomo also refers to a person who leads a crew of farmworkers, but from what I can tell mayordomo generally refers to a supervisor hired directly by a grower, and not an FLC.

Growers have good reason to consider obtaining workers through an FLC. They can leave the entire burden of paperwork, recruitment, transportation, housing, supervision, and payroll to someone else. But as some growers learn the hard way, thanks in large part to two special law offices in North Carolina, they can still be held liable and taken to court when those intermediaries break the law.[1]

It’s little surprise that mistreated H-2A farmworkers, some of whom are victims of outright human trafficking, are most likely to be among those brought here by an FLC. To make a profit, these intermediaries must cut costs wherever they can. Some might do so by blatantly disregarding the law on the calculated chance they won’t get caught. According to the US Department of Agriculture, much of the recent, explosive growth of the H-2A program is due to an uptick in hiring via FLCs. More disturbing is the gradual decrease in investigations by the Department of Labor into reports of employer rule violation and farmworker abuse, from more than two thousand per year in the early 2000s to less than half that in recent years.

It can be illuminating to see how the experiences of H-2A farmworkers differ across the US. In May 2022, PhD candidate Nathan Dollar conducted research at UNC Chapel Hill that sought to determine how living and working conditions of migrant farmworkers in North Carolina compare with those in California. A key part of his research involved interviewing workers from each state who worked the same crops: strawberries, raspberries, blackberries, and blueberries. The work itself, often backbreaking, is all but identical. So too are the grievances against employers whose behavior created poor working conditions. But that’s where the similarities end.

Nathan found pointed differences in the quality of life for workers doing the same jobs in both states, starting with the workers willingness to speak up. In California, 14 of 22 workers had directly confronted an employer. Out of 15 workers he interviewed in North Carolina, not one had.

In general, Nathan found, employers in North Carolina are under less pressure from the state to comply with labor regulations, which allowed them to flout those regulations with impunity. California also has considerably more agencies to assist farmworkers, has stricter workers’ compensation laws, and much stronger field sanitation requirements. And in 2016, California instituted the first and only policy in the nation requiring mandatory cooldown periods and employer-provided shade—policies that are increasingly important as global temperatures rise. North Carolina has no occupational safety and health policies beyond what is required federally.

Notable too is the striking difference Nathan found in how many berry workers were employed by a farm labor contractor in each state. In California, all interviewed workers were employed directly by owners of farms. In North Carolina, nearly all workers—14 of 15 Nathan interviewed—worked for a contratista.

Nationally, both growers and farmworker advocates have serious issues with the H-2A program. Growers would like to see limits placed on what they are required pay farmworkers and fewer limits on how they can put those employees to work. Advocates want to see those farmworkers provided the same labor rights as workers in other US industries and better protected against abuse. Says Diana Tellefson Torres of the United Farmworkers Foundation:

[1] Legal Aid of North Carolina and the North Carolina Justice Center

“The H-2A visa program has become the worst source of human trafficking among U.S. visa programs, deprives farm workers of basic freedoms, and subjects US and foreign workers to widespread violations of their rights.”

The chief complaint from many growers is the ever-increasing AEWR. The Department of Labor announces this minimum H-2A wage late each year. Aside from it almost always going up, growers don’t like how little time this gives them to budget for the next growing season, and they don’t like the methodology used to set the AEWR. As they must compete with foreign growers in countries where wages for comparable jobs are lower, US farmers sometimes have no choice but to absorb rising labor costs or go out of business. According to Leon R. Sequeira, attorney and adviser to growers and trade associations:

“Every time the Department of Labor drives up a farmer’s costs with mandatory increases in wage rates and other regulatory burdens, they put U.S. farmers at a greater competitive disadvantage in the international marketplace. And that leads to domestically grown produce being replaced on grocery store shelves with lower cost imports.”

There are other changes growers want to see. These include expansion of the program to year-round workers in all aspects of agriculture—not just those in crop fields and packing houses and nurseries—and visa periods longer than one year. They’d like a tax credit for the cost of housing farmworkers, a shorter period for making jobs available to US workers, and the removal of processing requirements that seem overly costly or unnecessary.

Daniel Costa, an attorney and researcher at the nonprofit and nonpartisan Economic Policy Institute, deems the industry outcry over the rising AEWR a false narrative. When considering inflation, the real value of that wage—that is, the wage you can buy things with—decreased by five cents. And he adds this:

“The 2022 average farmworker wage of $16.62 per hour is also just half (52 percent) of the average hourly wage for all workers in 2022, which stands at $32.00 per hour. The average hourly wage for production and nonsupervisory nonfarm workers—the most appropriate cohort of nonagricultural workers to compare with farmworkers—was $27.56 . . . In other words, farmworkers earned just under 60 percent of what [workers] outside of agriculture earned.”

Advocates also call attention to the illegal recruitment fees some workers must pay, oftentimes putting them in debt to the farm labor contractor who recruited them. By tying an H-2A contract to a single employer, the program generally denies workers job mobility. It also makes them reluctant to speak up about poor working or living conditions for fear of losing their jobs, conditions that can be extremely bad yet go overlooked due to ever-shrinking enforcement of labor laws.

As I write these words in early 2025, with the second Trump administration getting underway, many expect changes to US immigration policy in general and to non-immigrant visa programs like the H-2A in particular. Nobody can yet say what those changes will be. Certainly, our need for farm labor will not go away, at least not in the foreseeable future. Guestworkers are likely to keep filling this need, with more and more workers, mostly Mexican dads, leaving their wives, children, and parents for the better part of each year to do this hard work on our soil.

The H-2A program thrives because US citizens won’t take agricultural jobs at wages crop growers are willing or able to play, while plenty of citizens of Mexico are happy to work at those wages—and to endure living working conditions that many US citizens would never tolerate.

In his short story “The Semplica-Girl Diaries,” George Saunders invents a world that takes the concept of guestworkers to a dystopian extreme. In his world it’s okay—indeed, a sign of social status—to literally string up as lawn ornaments young women from an impoverished country, girls desperate to support their loved ones back home. Thankfully, it’s only fiction. And while H-2A farmworkers do not suffer like the girls in the George Saunders story do, the concept is the same. The differences are only a matter of degree.

Eva: I don’t like it. It’s not nice.

Thomas (rushing over with cat to show he is master of cat): They want to, Eva. They like applied for it.

Pam: Where they’re from, the opportunities are not so good.

Me: It helps them take care of the people they love.

—George Saunders, "The Semplica-Girl Diaries"