Chapter 3. Carolina Crops

Some expected and unexpected crops of North Carolina

“¿Qué tipo de cultivo están cultivando aquí?” I asked the men. What type of crop are you growing here?

We were huddled in the frigid and run-down trailer where these H-2A farmworkers cooked and ate their meals. It was early in the year and unseasonably cold. Two buzzing space heaters, sharing a single wall outlet in classic fire-hazard style, were all that kept us from shivering.

“How do you say, in English . . .” one of the men replied, practicing his emerging second language. He broke eye contact momentarily, the way people do when searching for a word, before answering. “Marijuana.”

“Really?” I thought he was pulling my leg. “You’re growing marijuana?”

“For medicine. Marijuana for medicine.” He answered as plainly as if I had asked his shoe size. He wasn’t kidding.

I was pretty sure, and would later confirm, that North Carolina did not allow anyone to grow marijuana in this state—for any reason. There was pending legislation to become one of the last states in the United States to allow the production and sale of medical marijuana, but nobody in this reliably red state was holding their breath.

Another of the men thrust a phone in front of my face. I noticed his brown fingers were weathered far more than mine, despite his being much younger. He used one to point to a photo. It showed endless rows of tiny potted cannabis plants filling a greenhouse, their jagged leaves recognizable to even to a fella like me with (almost) no experience smoking weed.

“¿Cuántas plantas hay?” I asked. How many plants are there?

“Siete mil,” one of them answered. Seven thousand.

“¿Un día? Un millón. Eso es lo que dice el patron,” he added. One day? A million. That’s what the grower says.

I gave this camp a nickname—Camp 420[1]—and wondered: Do these guys know growing marijuana here is illegal? Even for medical purposes? Did the grower bring them up from Mexico as a shield, so they would get busted after a raid instead of him?

Fortunately, within days I would learn my fears were unfounded. I knew the name of the grower these guys worked for and found it on a list of registered processors with the North Carolina Industrial Hemp Program. He was one of more than twelve hundred farmers growing hemp—not marijuana—in this state since doing so was legalized in 2017. The farmworker who boasted of soon growing a million marijuana plants was wrong—but it’s little surprise the distinction between hemp and marijuana got lost in translation, as it were.

Both hemp and marijuana plants belong to the genus Cannibis, and each is a strain of the cannabis sativa species. The practical distinction between them has to do with the level of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, in any given plant. THC is just one of the many elements, or cannabinoids, of cannabis. Another well-known cannabinoid is cannabidiol, or CBD. But THC is the one that gets you high.[2]

On my next visit to Camp 420, I did my best to explain the difference between the two plants. And to offer some advice about what to say the next time someone asked them what they are growing. “Responda ‘hemp,’” I advised them. “‘Marijuana,’ no.”

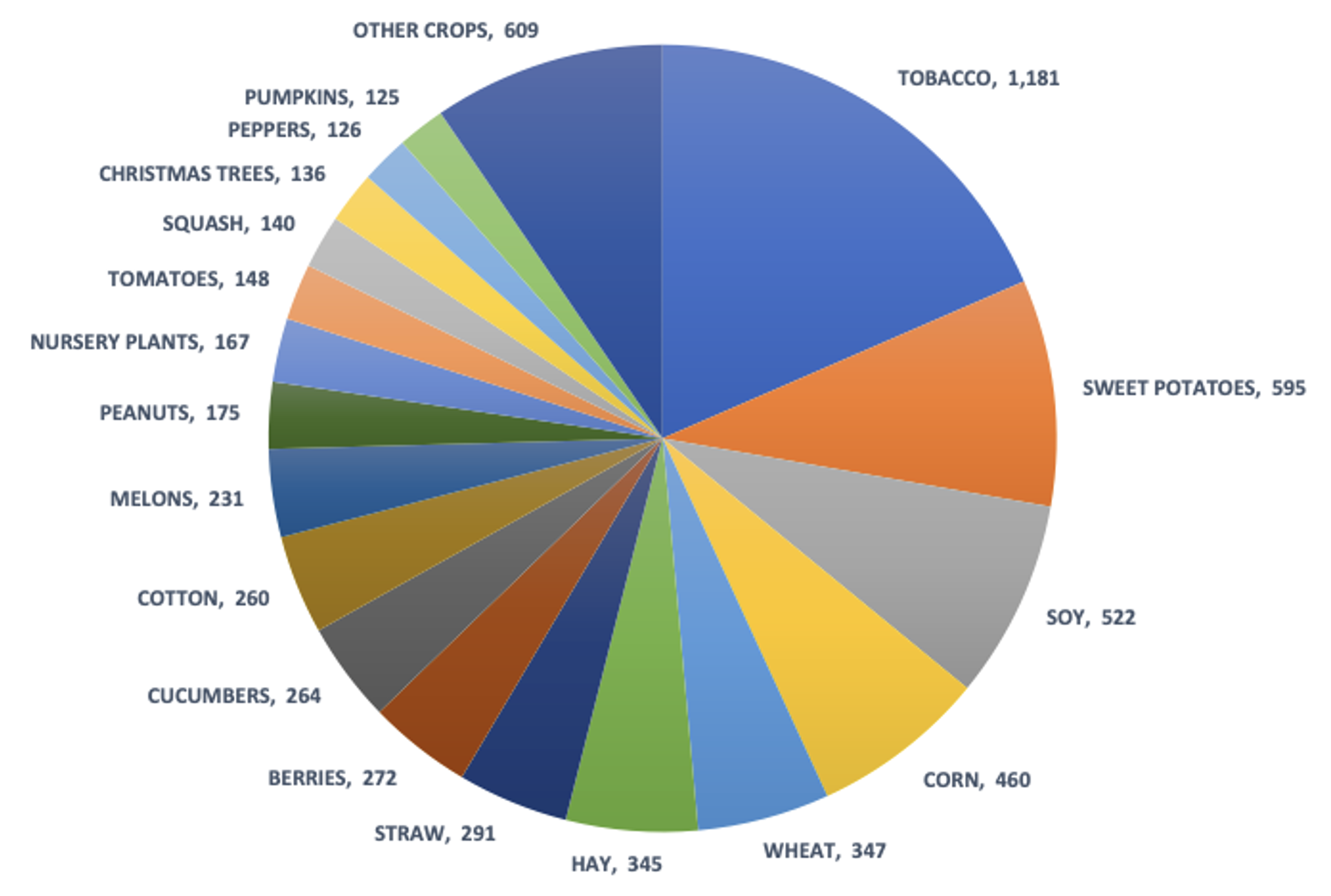

The unexpected exchange with the hemp farmworkers made me wonder: Do we grow a lot of hemp in North Carolina? Is it a specialty crop or something more? And how many crops do we grow around here, anyway? In the past, I might have guessed around a dozen: tobacco, sweet potatoes, melons, peppers, and other such items one sees in the grocery store. To get some idea of whether I was in the ballpark, I decided to look at H-2A job orders, which typically indicate which crops a farmworker will plant and harvest. It turns out my estimate was off by a lot. A whole lot.

Our tobacco and sweet potato crops are well known, and nobody would be astonished to learn this Southern state also grows cotton and peanuts. But our cornucopia (to use that word all but literally, for certainly the first and maybe the last time ever) brims with nearly eighty varieties of agricultural goodies, from apples to zucchini with peculiarities in the middle I had never heard of. Milo? It’s another name for sorghum, a type of grass used mostly for animal feed, ethanol production, and some human foods. Kenaf? North Carolina is apparently one of just four states where this cousin of okra and cotton is grown. Its fibers are used to make environmentally friendly products.

Tobacco is clearly king here. Based on H-2A job orders, nearly twelve hundred North Carolina growers requested workers for its planting, cultivation, and harvesting for the 2022 growing season. Sweet potatoes come in second and soy in third, with those three crops together representing roughly one-third of all crops for which growers need workers. Nearly another third of the seasonal workforce is needed for grains: corn, wheat, hay, and straw. The rest of what growers grow here is a mix of more than seventy different crop types.

[1] The number 420 is slang for marijuana, apparently from the time of day (4:20) at which some high school kids in San Rafael in the early 1970s would meet after school to smoke it. If you had to read this footnote, I suspect you are roughly my age.

[2] THC is THC whether it’s from hemp or marijuana. Its effect is based on the quantity consumed and not its source. My wife, Becky and I found this out the hard way after purchasing some perfectly legal Delta-9 chocolates from the Cannabliss Dispensary in Chapel Hill, disregarding warnings from the knowledgeable staff there and downing them whole. We got astonishingly stoned. The story of the ensuing euphoria and hallucination, and eventual panic by us THC newbies, is on my blog.

Tobacco is more than just the leading crop around here. North Carolina produces more of it than any other state—by a considerable margin. Growers here produced two hundred fifty-two million pounds of flue-cured tobacco in 2022, or 80 percent of the US total. Our 2022 harvest was considerably less than in earlier years, such as the 383 million pounds of 2007, due in no small part to the decline in cigarette sales. In 1997, smokers in North Carolina bought nearly 920 million packs of cigarettes. By 2020, that number had fallen nearly in half to 524 million.

Another reason for the decline in tobacco production is the historic buyout of tobacco farmers starting in 2005. In the 1930s, to help struggling tobacco farmers, Congress artificially controlled the price of tobacco by setting limits, or quotas, on how much tobacco could be legally sold in the United States. If you think of a natural market price as the meeting place of supply and demand, then you can imagine how capping the supply will keep a price from falling, especially when demand goes up, as it certainly did throughout the middle of the twentieth century.

Existing tobacco farms were given allotments that specified how much they could sell each year. A farmer choosing not to grow tobacco could effectively lend their allotment to another farmer, hence these tradeable financial commodities became extremely valuable to a farmer, arguably more valuable than even their land. This all came to an end in 2004 when Congress enacted the Tobacco Transition Payment Program, in which the government would buy back all those allotments for $10 billion collected from new assessments on sellers of tobacco products. The disappearance of allotments, and the new volatility of tobacco prices, which were thereafter free to fluctuate with supply and demand, gave plenty of tobacco growers a reason to consider getting out of the business.

Also contributing to the decline in tobacco production was the emergence of a scientific fact. North Carolina’s leading crop has no nutritional value. Indeed, it’s toxic, killing many of its consumers even when used exactly as intended. Of course, we didn’t know for sure that smoking killed people until we had been growing it for a few hundred years, by which time our agricultural economy rather depended on it.[1] Nowadays, vaping is the preferred means of consuming nicotine—the addictive part of tobacco—for more and more consumers. But nicotine is just as addictive when vaped as when smoked, and emerging data indicates that vaping is strongly associated with chronic lung disease and asthma. In any event, no tobacco product out there is going to make a person healthier.

Farming tobacco is impossible without farmworkers. What do they do exactly? At the start of a season, they plant it. Midseason, they cultivate it by snapping off flowers and offshoots known as suckers. In the fall, they harvest, cure, and bale it.

Tobacco is sprouted from seed in a greenhouse from which it emerges in trays as tiny plants just a few inches tall. These trays are loaded onto giant transplanting machines on wheels. These machines have several seats where workers sit and transfer seedlings, one at a time, from a tilted tray to a horizontally spinning wheel, like a motorized Lazy Susan. As the machine moves down a plowed field, it injects these seedlings into the ground every few inches. The most important component of that machine, the one that cannot be automated, is the one where a human hand transfers those seedlings from a greenhouse tray to the feeder wheel. While this contraption rolls down a field, workers cannot pause for so much as a sneeze, lest there be a gap in a row of tobacco plants.[2]

The second key job is known as “topping and suckering” and comes several weeks after planting, when the tobacco plants are four or five feet tall and have started producing flowers at their tops. Plants are also around this time producing new shoots, known as suckers, in the joints where tobacco leaves meet the stalk. Both flowers and suckers take energy from the growing plant, energy better directed to the leaves. Hence, workers walk up and down rows for entire days, weeks at a time in peak summer heat, doing nothing but snapping off these flowers and suckers.

Growers finally need workers when the tobacco is ready to harvest. Lower stalk tobacco leaves mature before “upstalk” leaves do, so harvesting takes place in phases. First, lower stalk leaves are removed by hand or, increasingly, by a machine driven by a farmworker. Depending on where you live in North Carolina, this harvesting might be known as cropping, pulling, or priming. Whatever you call it, a week or so later, the middle leaves come off. And finally, the topmost leaves.

After each of these harvesting phases, the leaves are transported to a warehouse where workers pick out the bad ones and load the rest into metal curing sheds, or box barns. Green tobacco leaves go into perforated hampers inside these sheds. Workers then “pin it” by inserting rods into one side of the hampers and out the other, each separated by several inches. Once doors are closed, gas heaters go on. Then, over the course of several days, those green leaves turn into their distinctive golden brown or “bright leaf” color, with the rods allowing drying air to circulate as they shrink.

When curing is done, workers remove the rods and dump out the leaves, pick out anything that isn’t a good leaf, then get the tobacco into machines that press it into bales, each weighing around three hundred pounds. Trucks will ship these to a buyer such as Philip Morris or Altria, with whom the grower has signed a contract for the delivery of a certain quantity and grade of tobacco at a fixed price.

One of the last things workers do is drive machines up and down the tobacco fields to remove the denuded stalks and plow the ground into a new row of dirt for next year’s planting—but not of tobacco. It’s common practice to rotate crops from year to year so as not to deplete a given field of certain nutrients, and to inhibit the buildup of disease-causing organisms, or pathogens. This need to rotate helps to explain the second most common crop in North Carolina.

Given its long regional presence, its key role in our agricultural economy going back to Colonial times, and the mass popularity of smoking for most of our country’s history, it’s easy to see why tobacco remains North Carolina’s top crop. But what gives with sweet potatoes? As with tobacco, more sweet potatoes come out of the ground here than in any other state. But King George III did not send English colonists here to grow these fleshy tubers so Brits could get hopped up on candied yams. And while they are a Thanksgiving dinner favorite of many an American (starting with this one), they are not chemically addictive. So why do we grow nearly as many pounds of sweet potatoes as we do tobacco? The chief answer is, well, tobacco.

Both tobacco and sweet potatoes grow well in the sandy loam soil of eastern North Carolina. And, as with tobacco, farming sweet potatoes is all but impossible without farmworkers. At the start of a season, they ride transplanting machines to get the plants into the ground, carefully moving each seedling from a tray to a moving wheel. There is no topping or suckering to do with sweet potato plants, but their harvest is even more dependent on farmworkers than is that of tobacco. With tobacco, there are machines nowadays to harvest leaves. With sweet potatoes, machines can only begin the harvesting process by plowing under rows of mature plants to bring ripe tubers to the surface.

Wayne Sanderman grows tobacco, sweet potatoes, and a handful of other crops on five thousand acres in Pitt County. In the fall each year, he gets out of bed at 4:30 in the morning to unearth his sweet potatoes. “They’ll store for twelve months if you harvest them properly,” says Wayne. He explained to me how the machine digs up each sweet potato, runs it over a bit of chain to shake the dirt off, then deposits it on the ground. But it can’t stay like that for long, especially if it’s a hot day and certainly not if it rains. That’s why he starts his day so early.

Once the sweet potatoes are unearthed, human hands must pick them up, one at a time. Because of the delicate skin of a sweet potato, no machine can yet do that as well as a person can. Virtually every sweet potato you pluck out of a bin at a supermarket was plucked off the ground by a farmworker, performing classic “stoop labor,” as this kind of field work was once known, and then tossed into a harvesting bucket. When that bucket was full, the worker hurried it to a nearby truck and tossed it up to another worker, who emptied it and tossed it back down, so its owner could hurry back to fill it again.

If you’re a tobacco farmer, with a camp full of farmworkers here already, then why not rotate your tobacco with another crop that depends on farmworkers?

“Rotation with sweet potato makes a lot of sense because both of these crops are high-labor-input crops,” according to Jonathan Schultheis, a horticultural scientist at North Carolina State University and sweet potato specialist. “Thus, there is the ability to keep labor busy on a given farm, and this fits well [into] the H-2A program.”

In other words, the sweet potato is our number two crop because tobacco is number one.

It’s been a few decades since North Carolina got serious about growing the sweet potato, which is only distantly related to a potato. Scientifically, it belongs to the Morning Glory family whereas a potato belongs to the Nightshade family. And the sweet potato is not even distantly related to the yam, despite the US Department of Agriculture requiring anything labeled yam also be labeled sweet potato. Whatever.

Over the years, growers and scientists at NC State University’s agricultural extension program have become quite good at refining the production of sweet potatoes. In the early 2000s, those scientists invented an all-new variety, the Covington, which now dominates the market for its resistance to pathogens, pleasing shape, and other such qualities. Extension scientists and growers have also learned how best to clean, cure, and store these staples after harvest. In the 1970s, nearly half the sweet potatoes harvested never made it to market due to the natural decomposition and rotting. Now, something like 95 percent does. More important, as grower Wayne Sanderman pointed out, sweet potatoes can be sold for up to a year after harvest, so they’re no longer regional nor seasonal. This staple can be found in stores all year long and all over the world.

North Carolina is nearly as serious about the sweet potato as it is about tobacco. We declared it our state vegetable in 1997. More recently, our state legislature showed it is not bashful about exercising our authority in all things related to the sweet potato by changing the very way it is spelled. Or at least the way they think it should be spelled. With the North Carolina Sweetpotato Act of 2020, the vegetable once referred to in state documents using the two words sweet potato would henceforth be known as the one-word sweetpotato. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary still spells it as two words. But here, to our lawmakers and agricultural lobbyists, efficiency is apparently everything when it comes to these dinner table favorites. There is no time even for a space between words.

[1] Even when the Surgeon General declared tobacco deadly in 1964, we debated it for a few more decades before passing laws aimed at reducing its consumption, especially among young people. Congress gave the Food and Drug Administration authority to regulate tobacco products only in 2009.

[2] Farmworkers on foot, walking behind the machine, keep an eye out for any gaps and quickly fill each one from their own supply of seedlings.